“The impression made on memory will also be such as never afterwards to be obliterated; for the new art of memory is by association, … here the words and the pictures correspond as much as possible.” – Robert John Thornton, Illustrations of the School-Virgil

from Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes [i]

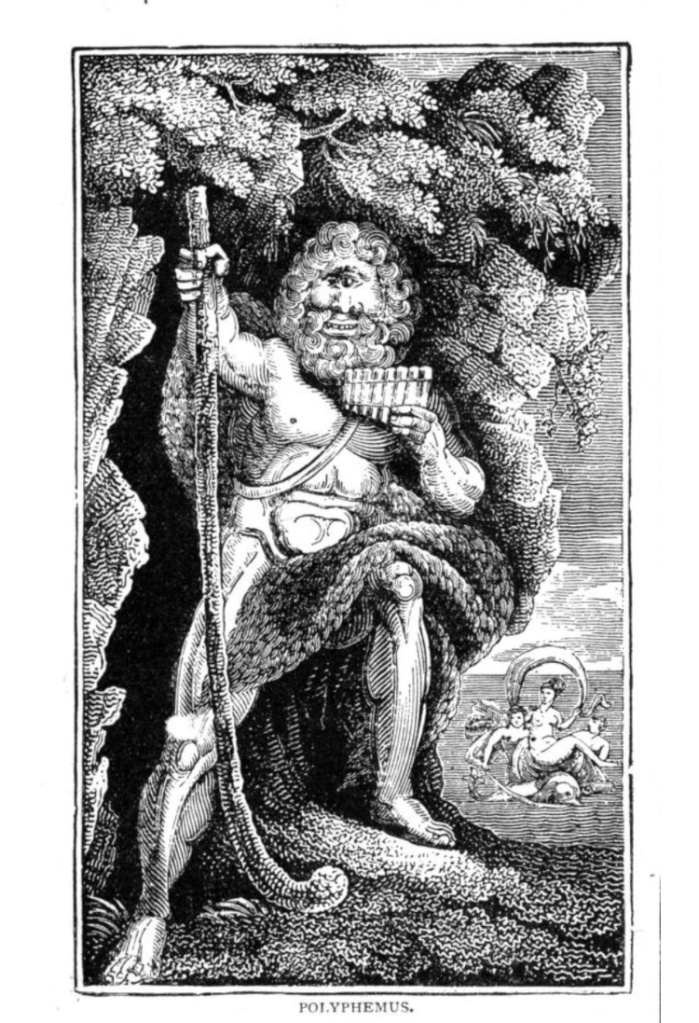

The title page of Supplement IV: Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes (1976) presents the reader with an unattributed illustration depicting the cyclops Polyphemus and the sea nymph Galatea. The treatment follows the ‘unrequited love’ telling of their story in Theocritus’s 11th Idyll, [ii] rather than Ovid’s later version in Metamorphoses.[iii]

from 1,000 Quaint Cuts [iv]

As with Supplement IV, the same illustration is rendered without attribution, caption, or comment in Tuer’s 1886 compilation 1,000 Quaint Cuts. Above is a digital scan of the 1968 reprint of this book which is held at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.[v]

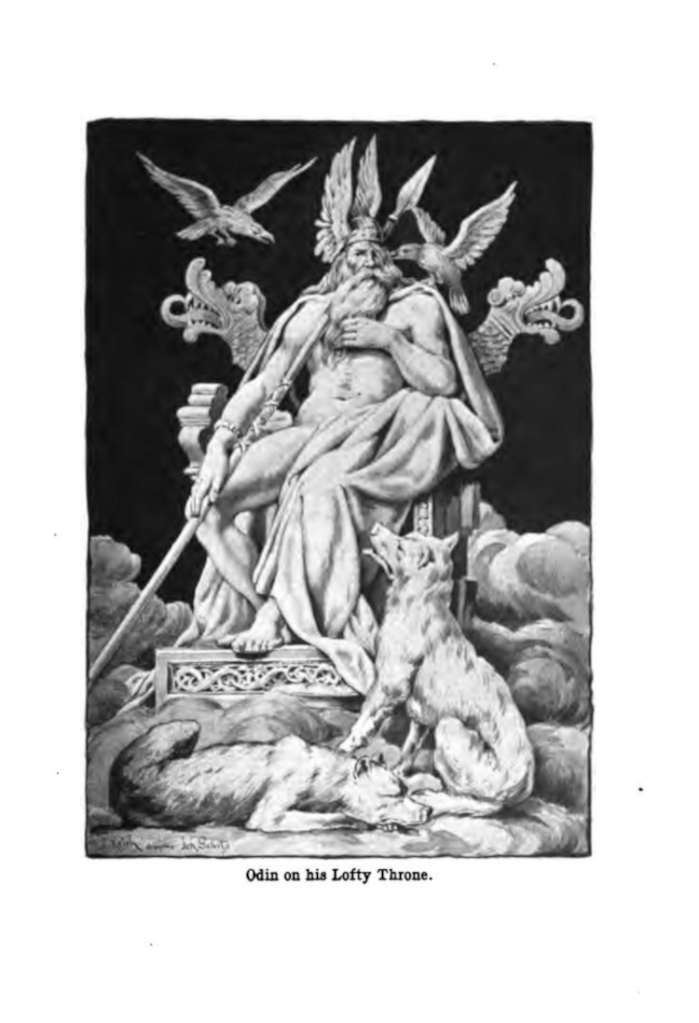

from Banbury Chap Books [vi]

We find the same illustration reproduced in Pearson’s 1890 collection Banbury Chap Books And Nursery Toy Book Literature. Here, the editor has included a caption reading “Cyclops, from ‘Thorton’s Virgil,’ circa 1810. In the Preface it is stated, Wm. Blake designed, and Branstone engraved the above,” a description misstating critical information, as we will see below.

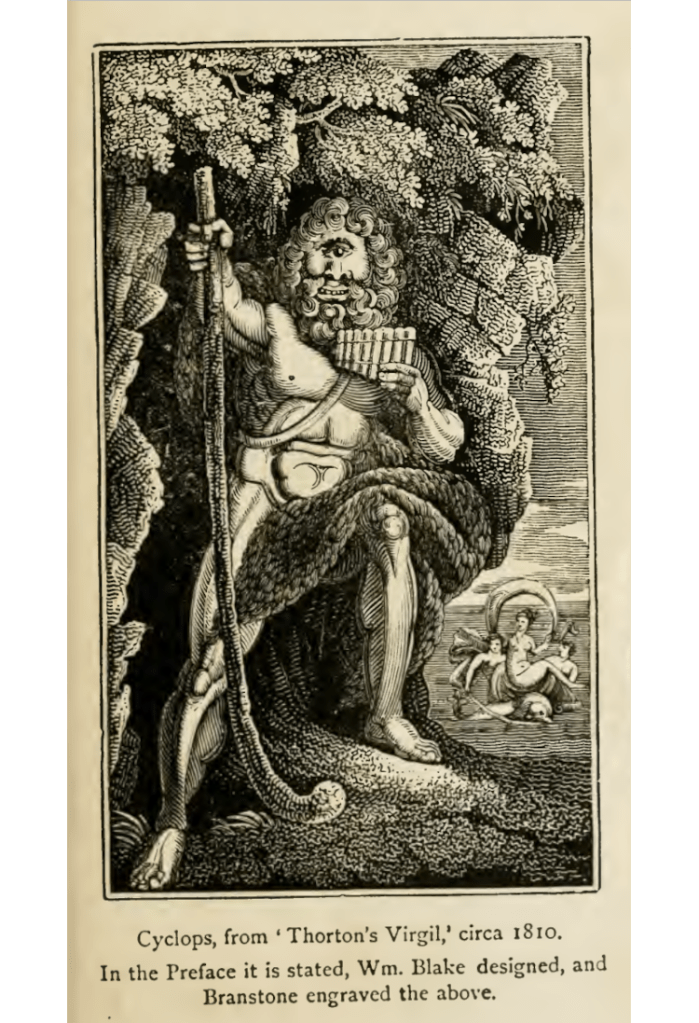

from The Strand Magazine, No. 20 [vii]

Finally, in 1892, The Strand Magazine also reproduces the illustration, this time identified as a “representation of Polyphemus, at the entrance to his cave, with cloak, staff, and Pandean pipes. The bold, free drawing of the King of the Cyclops is of the school of Blake, but there are points in the execution which diminish the probability of its being Blake’s actual work.” And which description again, except for accurately naming the cyclops as Polyphemus, perpetuates the misrepresentation.

Title Page of Thornton’s 1812 School Virgil [viii]

The continuing misrepresentation in various reprints is understandable. Robert John Thornton’s “Virgil” went through three editions, in 1812, 1814, and 1821—and copies are scarce. The title page of the 1812 edition, stereotyped and printed by David Cock and Co., and titled School Virgil, is pictured above. In 1814, Thornton would later publish the supplementary Illustrations of the School-Virgil with F.C. and J. Rivington. That same year he would also publish through Rivington a second edition combining text and illustrations.[ix]

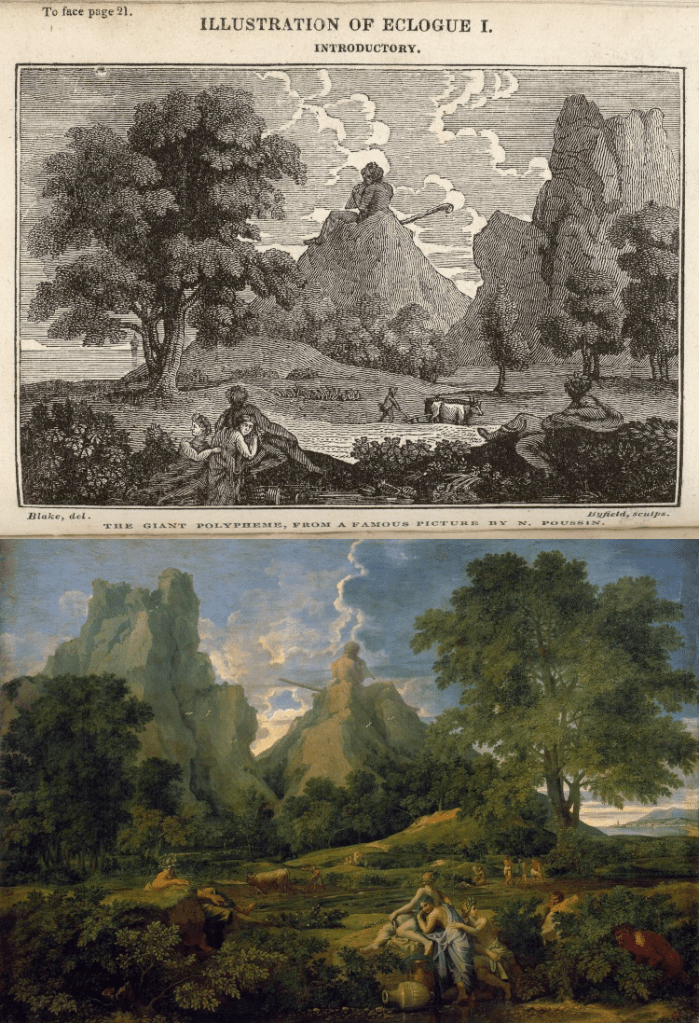

from The Pastorals of Virgil (1821) [x]; and Poussin’s Landscape with Polyphemus (1649) [xi]

In 1821, Thornton expanded and retitled the work as The Pastorals of Virgil. For this third edition he was able to engage William Blake through a mutual friend for a number of woodcuts and copper-plate engravings, and as designer of some illustrations executed by other hands. It is important to note that prior to this edition, the set of illustrations did not contain any by Blake, who was not engaged with the work until 1820.[xii]

The engraving above, captioned “Illustration of Eclogue I. The Giant Polypheme. From a Famous Picture by N. Poussin. Blake, del. Byfield, sculps.” mirrors Nicolas Poussin’s composition in “Landscape with Polyphemus” (1649).

The Banbury reprint, other than misspelling the names of Thornton and Branston,[xiii] and The Strand both appear to have confused the above ‘engraving by Byfield[xiv] from a drawing by Blake of a figure of Polyphemus by Nicolas Poussin’[xv] with the original illustration of Polypheme below.

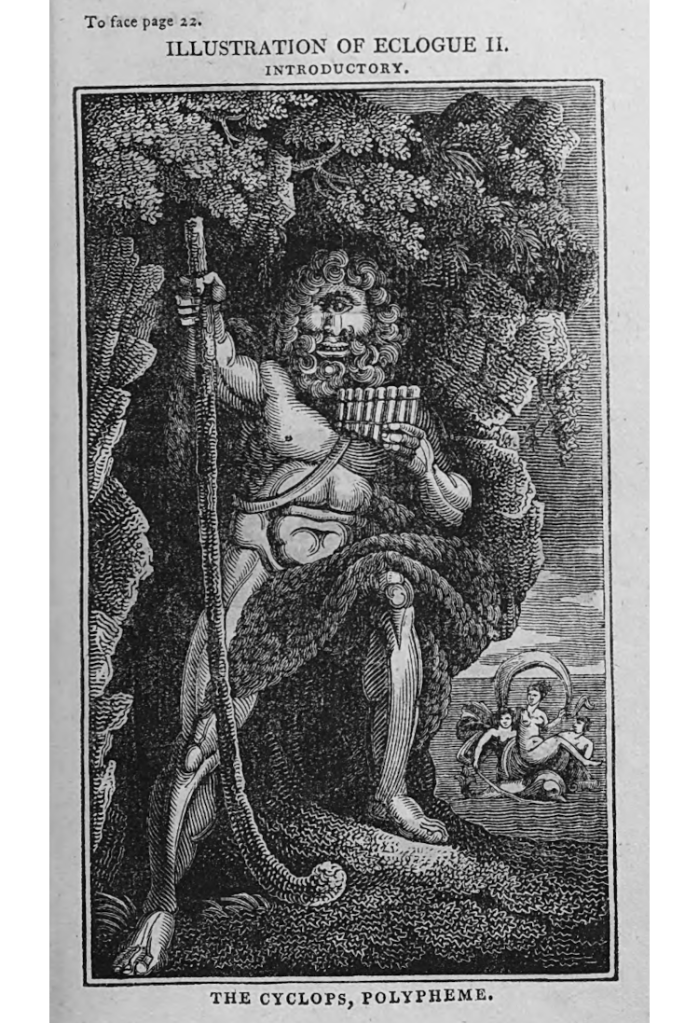

from Illustrations of the School-Virgil (1814) [xvi]

Captioned “The Cyclops, Polypheme” in the original 1814 Rivington print of Illustrations of the School-Virgil, the artist and engraver are still unknown.[xvii]

Several engravers and artists were involved in the set of original illustrations; however, the ‘Polypheme’ engraving does not appear reproduced in other available texts of the time by associated printers and publishers.[xviii]

In any case, where descriptions have accompanied reproductions of the original illustration, they perpetuated the same misrepresentation on down the line, confusing the engraving’s already murky origins.

As an interesting aside, among the artists who persuaded Thornton to include Blake’s unconventional woodblock engravings in the 1821 edition of The Pastorals of Virgil was the renowned English artist, James Ward (1769-1859).[xix]

[i] Ward, James, and Robert Kuntz. Dungeons & Dragons Supplement IV: Gods, Demi-Gods & Heroes. TSR Rules, 1976.

[ii] Theocritus; Bion; and Moschus. The Greek Bucolic Poets. Trans. J.M. Edmonds. London: W. Heinemann, 1912.

[iii] Ovid. Metamorphoses, II: Books IX-XV. Trans. Frank Justus Miller. London: W. Heinemann, 1916.

[iv] Tuer, Andrew W. 1,000 Quaint Cuts: from books of other days including amusing illustrations from children’s story books, fables, chap-books, &c., &c., A Selection of Pictorial Initial Letters & Curious Designs & Ornaments from Original Wooden Blocks Belonging to the Leadenhall Press. London: Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, 1886; republished by Singing Tree Press, 1968.

[v] Curiously enough, the Urbana-Champaign copy has library due dates indicating it was checked out for most of April and May 1976.

[vi] Pearson, Edwin. Banbury Chap Books And Nursery Toy Book Literature: [of the XVIII And Early XIX Centuries]. London: A. Reader, 1890.

[vii] Newnes, George. “Grandfather’s Picture-Books,” The Strand Magazine, No. 20. London: George Newnes, August 1892.

[viii] Thornton, Robert John. School Virgil: whereby boys will acquire ideas as well as words, masters be saved the necessity of any explanation, and the Latin language obtained in the shortest time. London: Stereotyped and printed by David Cock and Co., Published at the Linnæan Gallery, 1812.

[ix] Sung, Mei-Ying. “Teaching History or Retelling Ancient Stories with Pictures: William Blake and the School Version of Virgil,” The European Conference on Arts & Humanities 2017 Official Conference Proceedings. Japan: IAFOR, 2017.

[x] Thornton, Robert John. The Pastorals of Virgil: with a course of English reading adapted for schools: in which all the proper facilities are given, enabling youtm [sic] to acquire the Latin language, in the shortest period of time: illustrated by 230 engravings. London: F.C. & J. Rivington, Stereotyped and printed by J. M’Gowan, 1821.

[xi] Poussin, Nicolas. Landscape with Polyphemus. 1649.

[xii] Gilchrist, Alexander. The Life of William Blake. London: John Lane, 1907.

[xiii] Allen Robert Branston was an engraver also associated with the original prints.

[xiv] John Byfield per The William Blake Archive.

[xv] Russell, Archibald George Blomefield. The Engravings of William Blake. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1912.

[xvi] Thornton, Robert John. Illustrations of the School-Virgil in Copper-Planes and Wood-Cuts. London: F.C. and J. Rivington, 1814.

[xvii] For an interesting comparison of composition of the figures, see Carlo Cesio’s 1657 engraving of Polyphemus and Galatea after Annibale Carracci’s 1605 fresco in the Palazzo Farnese (The Loves of the Gods).

[xviii] Printing from stereotype plates was relatively rare in early 19th century Britain; by 1820 only a dozen printing firms in London did stereotyping. (“Andrew Wilson…”, from Jeremy Norman’s History of Information). Anastatic reproduction wouldn’t arrive until 1841.

[xix] Gilchrist, Alexander. The Life of William Blake. London: John Lane, 1907.