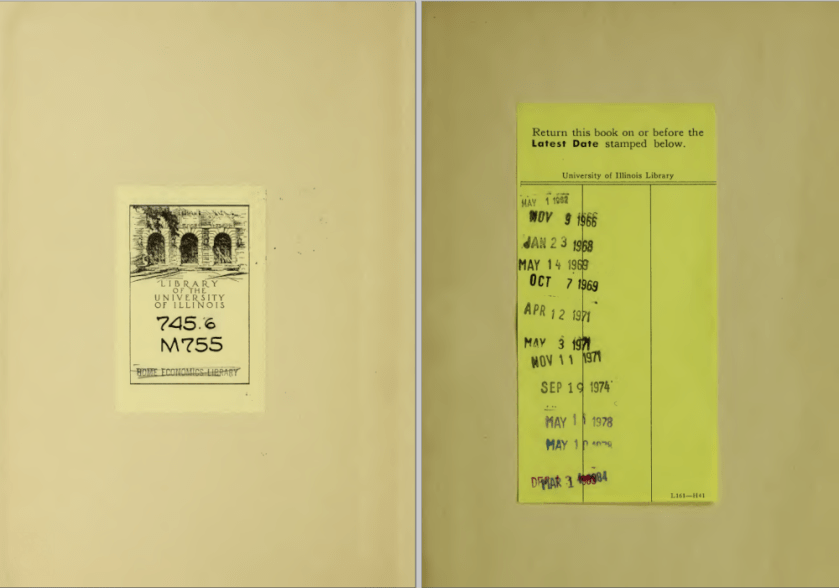

“Don’t touch that! You don’t know what forces you could unleash!” – Aleister Crowley to Grady McMurtry, attributed by Lon Milo DuQuette, in his Forward to The Book of Abramelin: A New Translation [i]

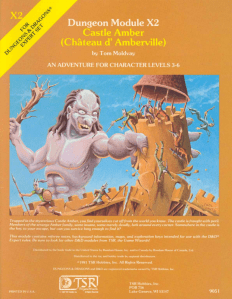

Cover of D&D module X2 – Castle Amber [ii]

In this article we will examine the occult source material of dungeon encounter #46 in the 1981 Dungeons & Dragons module X2 – Castle Amber. We will not venture to explain any occult significance of the encounter, neither do we presume any occult intent in its design choice other than as thematic ‘dungeon-dressing.’

Portrait of Clark Ashton Smith in 1912 [iii]

The influence of Clark Ashton Smith, Roger Zelazny, and Edgard Allan Poe in the module is readily evident. Other literary influences must include Baudelaire, “Flowers of Evil” (#22); Robert E. Howard, the narcotic black lotus (#50); and even a Norwegian Folktale, in the ‘Three Billy Goats Gruff’ encounter (#16).

From a Swiss (1JJ) Tarot deck [iv]

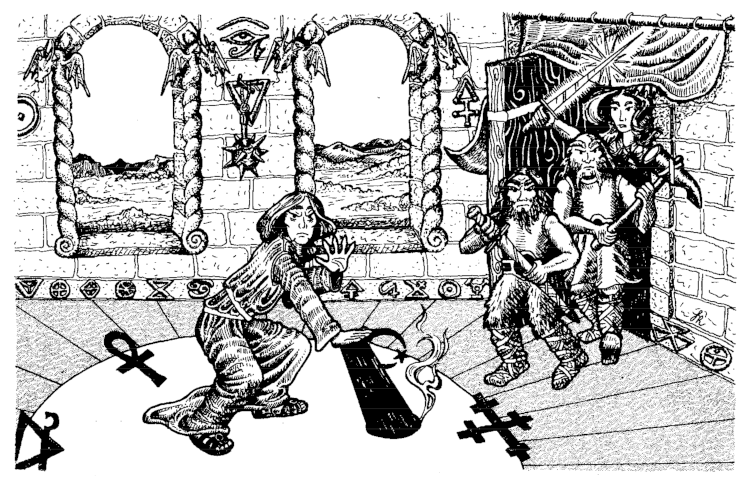

A surreal weirdness permeates the module, and it includes several generic occult-themed encounters, such as the Demon of Death (#53) and the Card Room (#38).[v]

from X2 Castle Amber

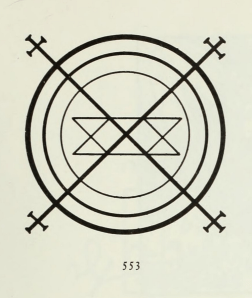

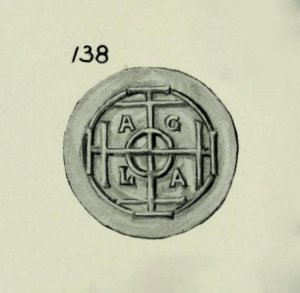

The Magic Letter Square (#46), the first room of the dungeon proper, presents a rather more unique and interesting encounter.

from X2 Castle Amber

The room description attributes several powers to the letter square, which may be ‘invoked’ either by traversing or standing on the square.[vi] In the encounter, the basic power of the square itself is lunacy, and, among beneficial effects, there are a couple of other possible ill effects, classified as curses, either blindness or lycanthropy.

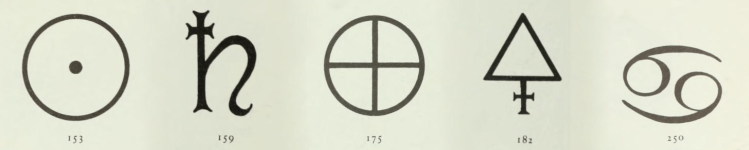

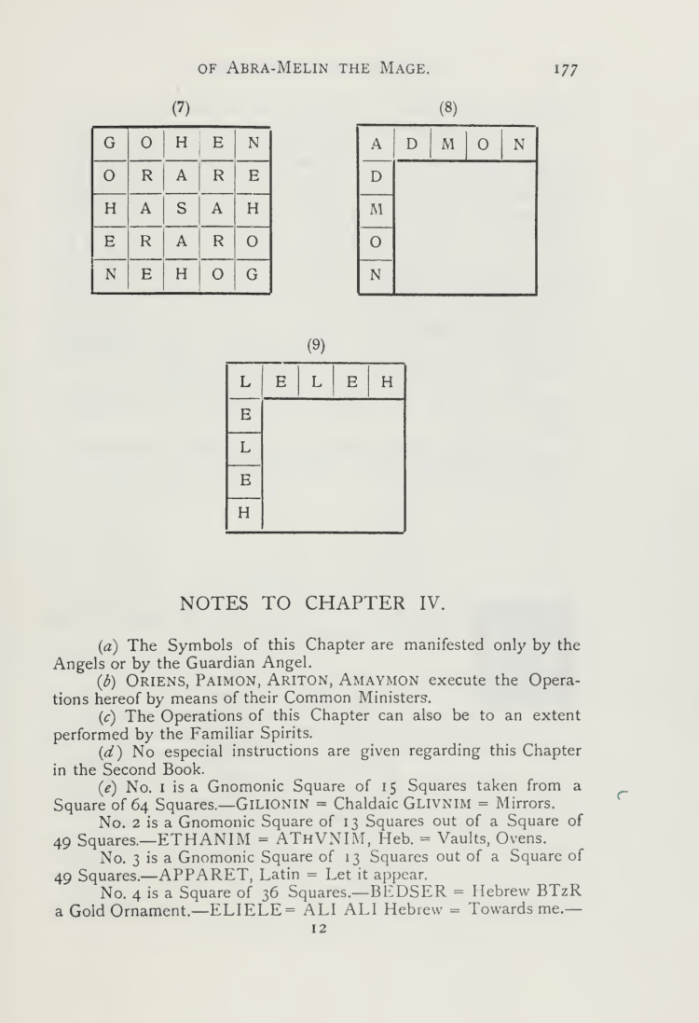

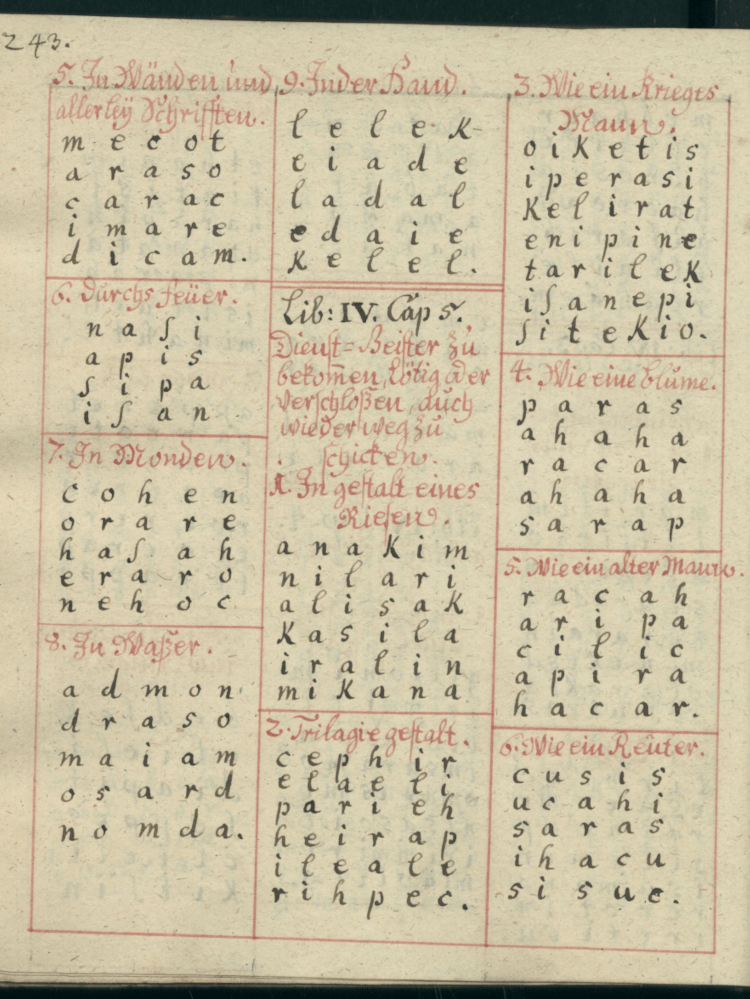

from The Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin the Mage [vii]

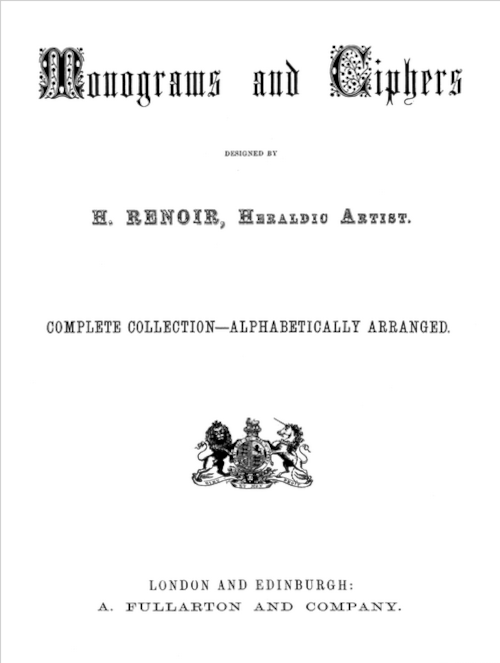

The form of this magic square is taken from The Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin the Mage, most likely S.L. MacGregor Mathers’ edition, which has been the only English-language translation available until quite recently. It is possible that there may have been another collection or encyclopedia of the occult used for reference as an intermediary text, but not necessarily so.

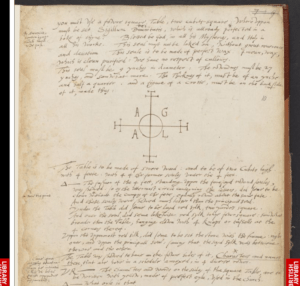

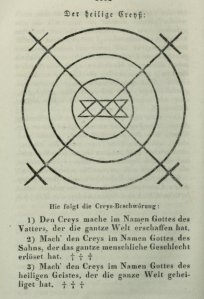

Pages from a French manuscript c.1750 at the Bibl. de l’Arsenal; and from the 1725 Peter Hammer edition

Mathers worked from an imperfect French manuscript—dated circa 1750—rife with errors, of which he was painfully aware.[viii] In his edition he reproduced the letters spelling GOHEN, although he commented in his notes that it should likely read COHEN. An earlier, German printing of the complete text—dated 1725—does give COHEN as the proper reading.[ix]

from the Dresden SLUB manuscript N 111 (c.1700)

An even earlier, circa 1700, German manuscript also appears intact and gives the spelling as COHEN for this square.[x] The earliest German manuscripts extant—no digital scan available—date from 1608 and are held at the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel. [xi]

George Dehn, in his contemporary, critical edition, proposes that the attributed author, Abraham von Worms, is a pseudonym of the historical Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha Levi Möllin, which would support an early 15th century composition.

Half-title page from The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin the Mage

The Abramelin text presents the magic word squares for use in dealing with spirits, and access to these abilities being earned only after great work. The COHEN or GOHEN square is intended for creating ‘visions in the moon.’ This textual association with the moon appears to be the only theme in common with the module’s assignment of the square’s powers to lunacy and lycanthropy.

Of course, the theme of traversing the magic square and running its risks to obtain some benefit suggests some similarity to traversing the Pattern in Zelazny’s Amber novels.[xii] As indicated at the beginning of this article, the module draws upon a wealth of literature, a testament as to how cultured and read was its designer.

“Nobody is born as a master—everyone needs to learn and to become a master—this is what happened to me and to everyone else. Engage yourself deeply in this study and you will be rewarded with experiences; the most shameful and disgusting title is ‘ignorant.’” – Abraham von Worms to his son Lamech, from the preface text to the 1608 manuscript, in Dehn’s edition

[i] Abraham von Worms. The Book of Abramelin: A new Translation. Edited by George Dehn, Translated by Steven Guth. Lake Worth, Florida: Iris Press, 2006.

[ii] Moldvay, Tom. Castle Amber. TSR Hobbies, Inc., 1981.

[iii] Portrait of Clark Ashton Smith. UC Berkely, Bancroft Library, By Unknown author, 1912.

[v] The encounter’s description appears to describe cards from a Swiss (1JJ) tarot deck, excepting the hand positions of the Juggler card.

[vi] N.B. The room description, taken literally, would indicate spelling out GOHEN only when a character commences traversing the square from the East on the bottom row, as directionally that series of letters is at the bottom—south side—of the square, rather than at the top.

[vii] Abraham von Worms. The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abra-Melin, the Mage. Translated by S.L. MacGregor-Mathers. Chicago: De Laurence, 1932.

[viii] La sacrée magie que Dieu donna à Moyse Aaron, David, Salomon, et à d’autres saints patriarches et prophètes, qui enseigne la vraye sapience divine, laissée par Abraham à Lamech son fils, traduite de l’hébreu. Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal. MS 2351.

[ix] Abraham von Worms. Des Juden Abraham von Worms Buch der wahren Praktik in der uralten göttlichen Magie und in erstaunlichen Dingen, wie sie durch die heilige Kabbala und durch Elohym mitgetheilt worden sammt der Geister- und Wunder-Herrschaft, welche Moses in der Wüste aus dem feurigen Busch erlernet, alle Verborgenheit der Kabbala umfassend. Köln am Rhein: Peter Hammer, 1725.

[x] Magia Abraham oder Underricht von der Heiligen Cabala. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden (SLUB), Mscr.Dresd.N.111.

[xi] Abraham eines Juden von Wormbs Magia (Cod. Guelf. 10.1 b Aug. 2°; Heinemann-Nr. 2112) and Abrahams, eines Juden aus Worms, des Sohnes Simons, Buch der alten Magie (Cod. Guelf. 47.13 Aug. 4°; Heinemann-Nr. 3488). And a 17th century Italian manuscript is held at the Biblioteca Queriniana in Brescia.

[xii] Zelazny, Roger. Nine Princes in Amber. New York: Doubleday, 1970.